When “anyone” can translate – bringing in the experts

- Emily Feng

- February 29, 2016

- 5,510 views

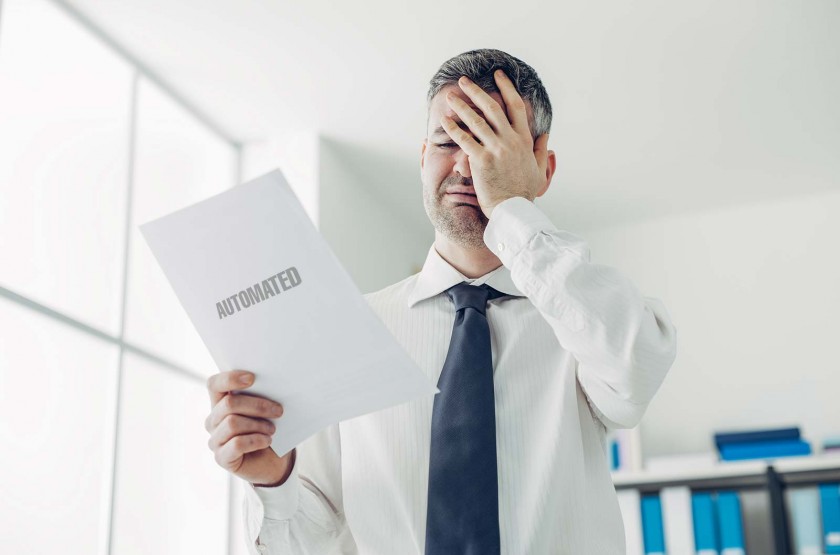

The translation industry is currently facing a dilemma: how do we make translation more accessible?

For smaller businesses in need of globalized content, high quality human translation for their business-facing content can still be a prohibitively resource-intensive service. For would-be translators, translating tools and workflow processes are now so technical that a lot of bilingual talent goes untapped.

Stepes has introduced a mobile-only solution that promises to allow more bilingual speakers to participate in translation. However, like all disruptive technologies, Stepes has attracted speculation about how it will maintain translation quality. One critic responded to Stepes’ “Uber” model of translation with the following:

If we follow [Stepes’ founder] Carl Yao’s logic anyone who drives a car can be a mechanic, anyone who plays the piano can be a concert pianist, and anyone with two hands who can distinguish an arm from a leg can be a surgeon.”

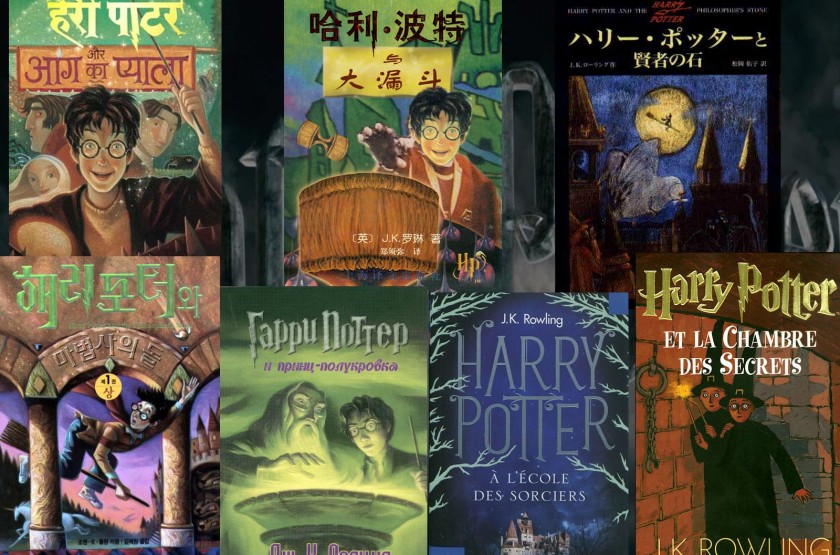

While this comment seems to make sense by itself, it misses Stepes’ real mission, which is to empower the world’s large bilingual population who already specialize in specific subject matter fields such as medical, legal, financial, engineering and other professional domains. Stepes opens up the translation process to bilingual subject matter experts, those who are already in command of both language skills and domain expertise, two of the most important qualifications for translating. So the answer is yes that a bilingual auto mechanic can translate content such as the auto repair manual, and a bilingual neurosurgeon can translate medical content related to the diagnosis and surgical treatment of disorders of the central and peripheral nervous system.

Of course, translation quality is a huge concern for any new translation venture, because quality is the major differentiator that still gives human translation a significant edge over machine translation. Stepes simplifies the translation process and makes translation easily accessible so the world’s large pool of untapped language talent can now get involved, improving translation’s quality and efficiency so more businesses are able to translate for global growth.

Let’s go over how Stepes works again very quickly. Unlike its predecessors, Stepes is a mobile-only translation tool, and its chat-based translation interface streamlines the translation process to allow translation to happen on-the-go anytime and anywhere. This streamlining, combined with the automation of some of translation’s more bureaucratic processes, also drives down overhead costs so clients pay less for translation. Stepes is able to pass on these savings downstream to the translators themselves, so that translators earn just as much if not more compared to other translation companies. (Check out this article here for more information about how much Stepes pays its translators)

One of Stepes biggest claims is that because it is so easy to use and so accessible (global smartphone access has skyrocketed), virtually anyone bilingual is now able to translate. This claim has also attracted the most doubt.

Importantly, Stepes gives anyone bilingual the opportunity to participate in translation – as long as they pass certain standards. Moreover, as the uber of translation, Stepes translators are also rated at the completion of each project, holding them accountable for their work and ensuring the best translators gain more visibility. The success of Uber is a strong testimony to the beauty of the rating economy, and Stepes leverages the power of accountability to produce better translations. Most of Stepes translators currently come from an existing pool of 50,000 experienced translators gathered from translation management platform TermWiki. With a capable pool of translators acting as the seed for growing Stepes’ translator base, Stepes can ensure that future translations maintain high quality standards.

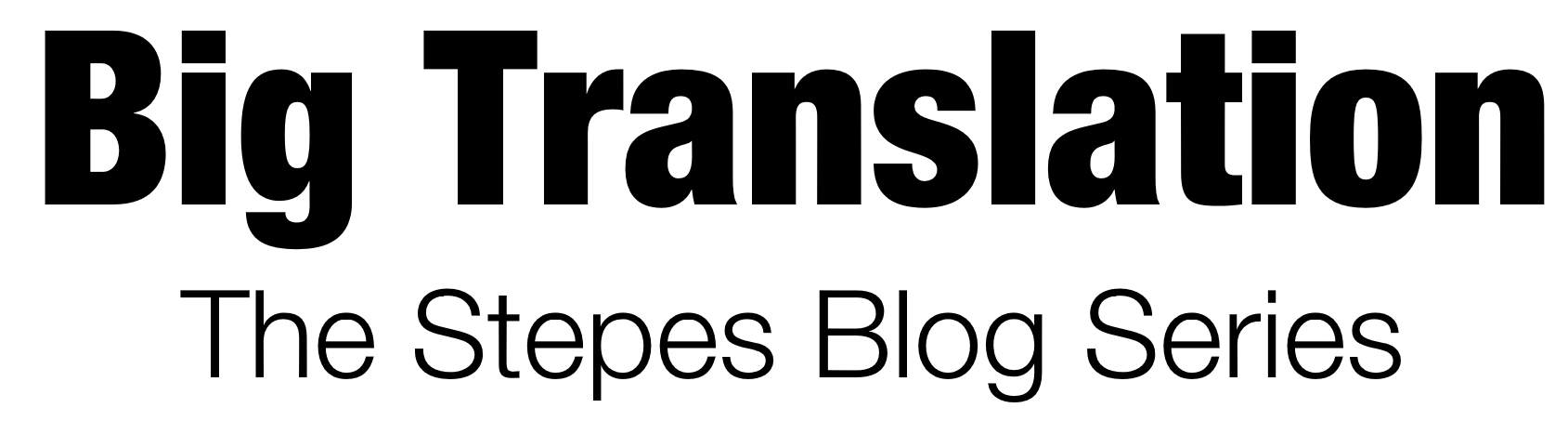

As mentioned already, Stepes is really designed to get more subject matter experts to participate in translation projects. Subject matter experts have expertise in a particular industry’s specialized jargon and procedures. Much of what urgently needs to be translated today is highly technical content: medical content, gaming dialogue, clinical trial support, product user manuals, and financial contracts among other things. We want give these bilingual industry specialists with insider knowledge of these growing areas in translation an opportunity to apply their professional expertise to producing more accurate translations. So, yes, we allow anyone bilingual to translate – especially if that someone also happens to be a subject matter expert.

Not everyone will be good at translation, but by giving anyone bilingual a way to translate from their smartphone, we can identify the best undiscovered talent. Even if only ten percent of the world’s 3.65 billion-strong bilingual speakers made for good translators, we would still drastically expand our global translation capacity.

Our logic is simple: the bigger the initial pool of bilingual talent you draw from, the more talented translators will emerge. The world’s current 250,000 professional translators out there cannot possibly encapsulate the only existing qualified translation talent out there; Stepes’ Big Translation approach is much more comprehensive net for finding talented translators and subject matter experts who have previously been stymied by the translation industry’s esoteric nature.

Long term, the goal of Stepes is to promote the study of language and translation. People who might never have considered translating on the side might use Stepes to become better and more frequent translators. Translation, just like any other profession, is a skill that must be learned and improved through practice. Stepes broadens the scope of who can even begin to become translators. Through careful training and quality control processes, we can begin identifying the best translation talent out there, regardless of whether these bilingual speakers were already professional translators with access to expensive software translation tools.

A more accurate description of Stepes’ modus operandi might be: a bilingual auto mechanic can become a talented translator of automotive user manuals, a concert pianist a translator of music history books, and a surgeon a much-needed translator of medical content. When it comes to delivering technically accurate translation, subject matter expertise trounces the ability to use complex translation tools.